Open Source Supply Chain Security

This article covers the growing issue of software supply chain security: what it is, the difference between vulnerabilities and attacks, current best practices, the institutional landscape, and emerging legislation.

Since there are more authoritative sources on the Internet, this article aims to provide an executive summary with key concepts and references to further reading.

What is Open Source Supply Chain Security?

Digital Supply Chain Security refers to the strategies and measures implemented to protect digital assets and processes (such as software) as they move through various stages of development, distribution, and deployment.

When focusing on open source, supply chain security becomes particularly challenging because of the communal and transparent nature of the development environment. Open source software often involves numerous contributors, some anonymous, and can be integrated into a wide variety of applications and platforms.

Open source supply chain security emphasizes:

- rigorous vetting of contributions

- continuous monitoring of dependencies

- prompt patching of known vulnerabilities

- community collaboration to maintain the trustworthiness of shared software resources

Components of the Open Source Supply Chain

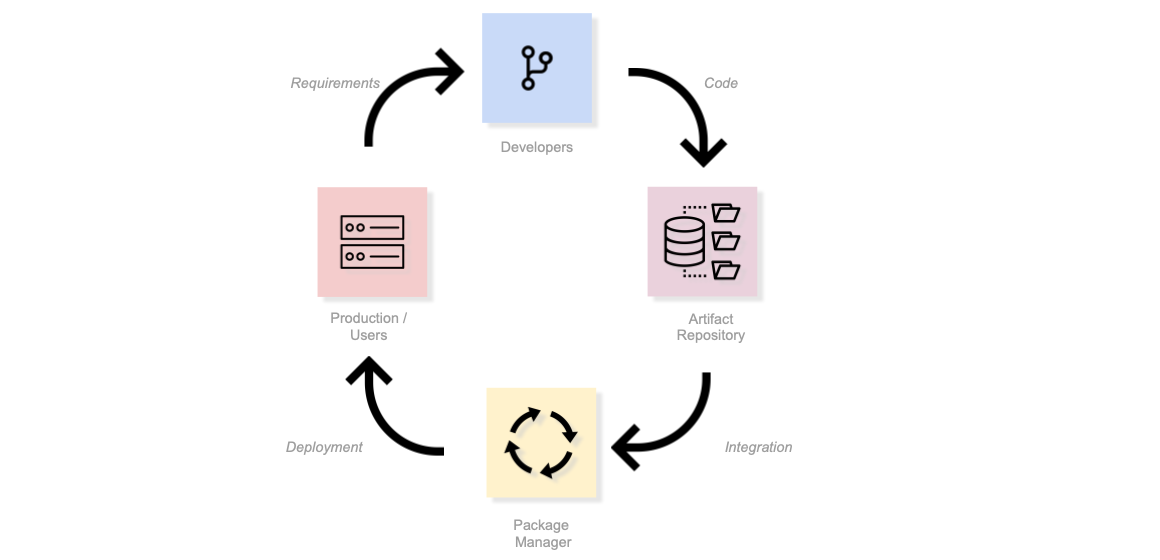

Attacks can occur at any point in the open source supply chain. The above diagram (adapted from "Open Source Software Supply Chain Security" by the Linux Foundation) shows the four main components, arranged in a cycle:

- Users: Individuals or systems that utilize software for various tasks and applications.

- Package Managers: Tools or software that automate the process of installing, upgrading, configuring, and removing software packages in a consistent manner.

- Repositories: Centralized storage locations or databases where software packages are archived, distributed, and made available for download.

- Developers: Individuals or teams responsible for creating, updating, and maintaining software codebases and packages.

Each of these is an opportunity for an attack. Critically, attacks also occur in the gaps between these components — the build processes, CI/CD pipelines, and automation that connect them. For example, the Shai-Hulud campaign (2025) exploited GitHub Actions workflows and npm preinstall scripts to spread malware through the spaces between developers, repositories, and package managers.

Vulnerabilities vs. Supply Chain Attacks

Understanding the difference between vulnerabilities and supply chain attacks is critical because they require different response timelines and strategies.

Vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities are accidental flaws in code that could be exploited by attackers. They may range from low impact to critical severity.

"Vulnerabilities are flaws in a computer system that weaken the overall security of the device/system. Vulnerabilities can be weaknesses in either the hardware itself, or the software that runs on the hardware." - Vulnerability, Wikipedia

Key point: Even if vulnerabilities exist in production, you typically have days or weeks to patch them before they're discovered or exploited. This is why regular patching cycles and vulnerability scanning are effective defenses.

See:

- Vulnerabilities in software are catalogued as CVEs.

- The MITRE ATT&CK aims to be a knowledge base of all the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used by attackers.

Supply Chain Attacks

Supply Chain Attacks involve malicious code that is intentionally introduced by an attacker into a package, dependency, or build process.

"A supply chain attack can happen in software or hardware. Cybercriminals typically tamper with the manufacturing or distribution of a product by installing malware." - Supply Chain Attack, Wikipedia

Key point: There is no grace period. You must catch malicious packages before installation, as the attack is active immediately upon use. This is why tools like Socket Security that analyze package behavior (not just known CVEs) are increasingly important.

Examples of High-Impact Vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities in widely-used frameworks and libraries can have massive downstream impact, affecting millions of applications simultaneously:

| Vulnerability | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Log4Shell (CVE-2021-44228) | Critical RCE vulnerability in Apache Log4j, a ubiquitous Java logging library. | Affected millions of Java applications; exploited within hours of disclosure. |

| Heartbleed (CVE-2014-0160) | Buffer over-read in OpenSSL allowing attackers to steal sensitive data from server memory. | Affected ~17% of all "secure" web servers; highlighted the "one maintainer" problem. |

| React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182) | Critical RCE in React Server Components affecting Next.js applications. | 77,000+ vulnerable IPs; exploited by nation-state groups within days. |

| CitrixBleed 2 (CVE-2025-5777) | Authentication bypass in Citrix NetScaler ADC/Gateway allowing session hijacking. | Mirrors the 2023 CitrixBleed; enables MFA bypass. |

| ToolShell (CVE-2025-53770/53771) | Chained exploit in SharePoint on-premises servers. | Exploited by Chinese APT groups; 396 systems confirmed compromised. |

| Oracle EBS (CVE-2025-61882) | Critical zero-day in Oracle E-Business Suite. | Exploited by Clop ransomware group for data theft and extortion. |

Examples of Common Supply Chain Attacks

| Attack Name | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency/Manifest Confusion | An attacker publishes a package with the same name as a private package used by a specific company but in a public repository. If the company's build system is not properly configured, it may pull the malicious public package instead of the intended private one. | Alex Birsan |

| Package Stealing/Hijacking | Attackers can sometimes take over abandoned or poorly maintained packages and introduce malicious changes. They then publish the updated malicious version, and dependent systems automatically pull in these updates. | us-parser-js above. |

| Malicious Forks/Masquerading | An attacker might create a fork of a popular open-source project, introduce malicious changes, and then attempt to promote or advertise this fork to unsuspecting users. | Stephen Lacy |

| RepoJacking | An attack where a malicious actor registers a username and creates a repository used by an organization in the past but which has since changed its name. Doing so results in any project or code that relies on the dependencies of the attacked project to fetch dependencies and code from the attacker-controlled repository, which could contain malware. | CTX |

| Piggybacking on Legitimate Packages/Pull Request Sneaking | Some attackers contribute malicious code to popular and legitimate projects, usually through pull requests. If not thoroughly reviewed, the malicious code might get merged into the main project. | Teleport |

| Download Count Inflation/Star Jacking | To make a malicious package look popular and trustworthy, attackers artificially inflate the download count. | Pampyio |

| Trojan Package | In the trojan package infection method, the attacker publishes a fully functional library but hides malicious code in it. | lemaaa |

| Joke Packages | Not strictly an attack, but publishing packages as jokes. Can harm the supply chain and cause dependency bloat. | true |

| Cache Poisoning | Exploiting weaknesses in parameter handling by package managers. | Rack |

| TypoSquatting | Typosquatting is the practice of obtaining (or squatting) a famous name with a slight typographical error. | "Amzon.com" |

| Long-Term Maintainer Takeover | Attackers spend extended periods (months or years) contributing to a project to build trust and gain maintainer authority, then insert backdoors or malicious changes from inside. Much more sophisticated than simple hijacking. | XZ Utils Backdoor (CVE-2024-3094) - "Jia Tan" built trust over ~2 years, then pushed a backdoor into liblzma |

| CI/CD Pipeline Compromise | Attacks that abuse build automation (webhooks, GitHub Actions, build jobs) to inject malicious code or steal secrets without touching the mainline source code. | AWS CodeBuild "CodeBreach" - misconfigured GitHub webhook filters allowed privileged builds from untrusted users |

| Wormable Supply-Chain Malware | Self-propagating malware that spreads through package ecosystems by infecting downstream dependencies via maintainer or automation compromise, then republishing infected packages. | Shai-Hulud Campaign (2025) - compromised hundreds of npm packages and spread via GitHub Actions |

| OAuth/SaaS Integration Abuse | Attackers exploit trust relationships between SaaS apps or OAuth integrations to steal tokens or pivot into customer environments, without attacking code or infrastructure directly. | Salesloft-Drift Token Theft (2025) - 700+ organizations affected via OAuth token compromise |

| Mass Maintainer Account Hijack | Attackers compromise maintainer accounts of high-traffic packages (via phishing or credential theft) to publish malicious updates to packages with large downstream usage. | chalk, debug, supports-color npm packages had malicious versions pushed after maintainer account compromise |

| Firmware/Update Mechanism Hijacking | Intercepting or redirecting legitimate software or firmware update channels to deliver malware to devices. | PlushDaemon/SlowStepper Campaign - network device update hijacking |

Once a package, even a legitimate one, becomes dependent on a malicious package, it might unknowingly propagate the malicious behavior when others use it.

Note: this table is just a list of notable examples. See The MITRE ATT&CK for a complete, authoritative list.

The Scale of the Problem

As the volume of open source software grows, the number of open source developers increases, and the cost of compute reduces, the importance of securing the open source supply chain becomes ever more critical.

"Supply chain attacks are increasing exponentially. In 2021 the world witnessed a 650% increase in software supply chain attacks, aimed at exploiting weaknesses in upstream open source ecosystems. For perspective, the same statistic was 430% in the 2020 version of the report." - State of the Software Supply Chain, SonaType

High-Profile Incidents

Several incidents have demonstrated the potential impact of supply chain security failures:

- SolarWinds (2020): Attackers compromised the Orion software build process, embedding malicious code in legitimate updates delivered to thousands of government agencies and corporations worldwide.

- event-stream (2018): A malicious actor took over maintenance of a popular npm package (>2m downloads/week), introducing a targeted payload that stole Bitcoin funds.

- left-pad (2016): A small JavaScript library was removed from npm in protest, unexpectedly breaking numerous dependent projects and highlighting the fragility of modern software dependencies.

The Exponential Growth of Vulnerabilities

The security landscape is becoming increasingly challenging due to the sheer volume of vulnerabilities being discovered and reported:

CVE volume is exploding. In 2024, over 40,000 CVEs were published — a 38% increase year-over-year. More than 20,000 had CVSS scores ≥ 7.0 (high or above), and over 4,400 were critical (CVSS 9-10). This volume makes it nearly impossible for security teams to manually triage every vulnerability.

Faster time to exploitation. Nearly a quarter (~23.6%) of Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEVs) are now being exploited on or before their public disclosure. Attackers are moving faster than security teams can respond.

Supply chain attacks climbing dramatically. Between 2021-2023, supply chain cyber attacks increased 431%, with projections pointing to continued sharp rises. In October 2025, supply chain attacks reached a new record high, 32% above the previous peak.

High blast-radius ecosystem attacks. Examples like the Shai-Hulud npm worm and maintainer hijacks of packages like

chalkanddebug(with billions of weekly downloads) show that a single compromise can cascade through millions of downstream projects and users.

This exponential growth means organizations can no longer rely on manual vulnerability management processes. Automation, prioritization frameworks (like EPSS - Exploit Prediction Scoring System), and proactive supply chain security measures are becoming essential rather than optional.

VEX (Vulnerability Exploitability eXchange) is an emerging standard designed to make SBOMs more actionable by providing context about whether a vulnerability is actually exploitable in a specific product or environment. A VEX document accompanies an SBOM and indicates one of several statuses for each vulnerability:

VEX helps organizations dramatically reduce false positives. For example, an SBOM might list dozens of CVEs in a dependency, but VEX metadata can clarify that most are "Not Affected" because the vulnerable code paths are never executed. This enables security teams to focus on genuinely exploitable vulnerabilities rather than drowning in noise.

VEX documents can be created using formats like CSAF-VEX or OpenVEX, and are increasingly supported by vulnerability management tools.

See:

- OpenCVE Statistics - real-time CVE tracking showing current vulnerability publication rates

- 2025 Supply Chain Vulnerability Report by Black Kite

- Cyble - Record Surge in Software Supply Chain Attacks

- FIRST EPSS - Exploit Prediction Scoring System

- CISA VEX Overview - guidance on VEX and SBOMs from the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency

- OpenVEX Specification - open standard for creating VEX documents

Transitive Dependencies

It is worth drawing attention to the issue of transitive dependencies. A developer may make use of up to fifteen (say) dependencies directly in a moderately-sized software application. However, each of these dependencies may have dependencies of their own and so on.

It is estimated that the average JavaScript dependency tree contains 86 packages, while for PyPI (Python libraries) it is 7.3. Research shows that on npm, each declared dependency brings in an average of 4.3× more indirect dependencies, with dependency chains averaging ~4.4 levels deep.

Compounding the risk, approximately 61% of npm packages have had no new release in the past 12 months, yet many continue to be widely downloaded — meaning unpatched vulnerabilities persist in actively-used code.

In 2016, Eric Wittern showed that not only was the number of npm packages growing exponentially (at nearly 200,000 packages by the end of 2016) but also the number of dependencies used by each package was increasing exponentially, going from zero in 2011 to nine in 2016.

By 2023, the number of npm packages was over three million. According to GitHub in 2020, although the average number of direct dependencies of a package is ten, the average number of indirect dependencies introduced as a result of those ten is 683.

See:

- How much do we really know about how packages behave on the npm registry? — Snyk's analysis of npm package behavior, abandonment rates, and dependency depths

- State of the Software Supply Chain — Sonatype's annual report on open source consumption trends and security

- JavaScript Growing Pains: From 0 to 13,000 Dependencies — An example of how easy it is to end up with 13,000 dependencies in a simple JavaScript application

Best Practices

As mentioned at the start of the article, this is a fast-evolving area. In this section, we'll outline a few important concepts that you should be aware of.

See:

- OpenSSF Best Practice Guides are a useful first stop.

- Linux Security Blog Article on best practices.

Software Composition Analysis (SCA)

According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_Composition_Analysis:

Software Composition Analysis (SCA) is a practice in the fields of Information technology and software engineering for analyzing custom-built software applications to detect embedded open-source software and detect if they are up-to-date, contain security flaws, or have licensing requirements.

See Also:

- Many SCA tools produce SBOMs which can then be checked for vulnerabilities.

- A long list of SCA tools is provided here: https://todogroup.org/guides/management-tools/#tools-for-managing-source-code

- Dependabot on GitHub

Static Application Security Testing (SAST)

SAST, or Static Application Security Testing, is a type of software security testing that analyzes the source code of an application for potential security vulnerabilities without executing the code.

"SAST is a vulnerability scanning technique that focuses on source code, bytecode, or assembly code. The scanner can run early in your CI pipeline or even as an IDE plugin while coding. SAST tools monitor your code, ensuring protection from security issues such as saving a password in clear text or sending data over an unencrypted connection." - Static Application Security Testing, Snyk

Some leading SAST tools are Checkmarx, Veracode, SonarQube, Fortify and Coverity.]

See Also:

- Socket Security - a GitHub App for performing SAST

- CodeQL also built into GitHub's Action system.

Dynamic Application Security Testing / Penetration Testing

Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST): DAST involves executing the code of an application and examining its behavior for potential security vulnerabilities. This type of testing can help identify potential security risks that may not be apparent from examining the code alone.

Penetration Testing: Penetration testing involves attempting to actively exploit vulnerabilities in a software system or application to determine its security weaknesses. This type of testing is usually conducted by security experts who use manual and automated techniques to simulate real-world attacks.

Tools for these include Metasploit, Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP), Fortify WebInspect and Burp Suite.

See:

- Penetration Testing Reviews and Ratings by Gartner.

- DAST Tools.

Infrastructure Security Testing

Infrastructure security testing involves evaluating the security of the underlying infrastructure that supports a software system or application, such as networks, servers, and databases.

Some leading tools include Nessus, Nmap and Qualys

Attestation / Signing

Via the use of secure hashes and digital signatures, it's possible to prove that code was either authored by someone ("provenance attestation") or built by something ("build attestation").

This is useful when producing or consuming open source software.

Developer Best Practces

Linux Security suggests:

- Using multifactor authentication on developer accounts.

- Having a formal change-tracking process.

- Giving each release a unique identifier.

- Testing for bugs and unexpected behavior throughout the development cycle.

- Documenting and managing a project’s dependencies.

- Cryptographically signing a project’s integrity (attestation, above).

- Checking digital signatures of dependencies.

- Checking for signature revocation (just checking attestation is not enough).

- Tracking and addressing vulnerabilities in open-source tools used in development.

... many of which are contained in the OpenSSF best practices (see below).

Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR)

Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) is a cybersecurity solution that continuously monitors and analyzes endpoint data to detect, investigate, and mitigate advanced threats across a network.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endpoint_detection_and_response

Web / Mobile Application Security Testing.

- Web Application Security Testing: Web application security testing focuses on identifying security vulnerabilities in web applications, such as SQL injection, cross-site scripting (XSS), and cross-site request forgery (CSRF).

- Mobile Application Security Testing: Mobile application security testing focuses on identifying security vulnerabilities in mobile applications, such as those running on iOS or Android platforms.

See:

- Consider Gartner's Application Security Testing summary page. Lots of overlap in the tools between many of these categories.

Initiatives / Industry Bodies

- Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) program, to catalog vulnerabilities. See also CVE Article.

- National Vulnerability Database (NVD) program, another vulnerability catalog, run by NIST.

- OSV - synthesises CVEs fom the databases for a given commit hash.

OpenSSF: A foundation (part of LF) devoted to the securing the open source ecosystem. Most of its projects are hosted on GitHub. Projects of note include:

- GUAC: Graph for Understanding Artifact Composition

- Best Practices Working group: publishes best practices around hosting open source projects, issuing badges for meeting their criteria.

- Digital Identity Attestation: an initiative for allowing contributors to sign open source code.

- AllStar: A GitHub App for heuristically testing best practices around open source governance.

- CVE Schema Standard format for reporting of CVEs.

The MITRE ATT&CK aims to be a knowledge base of all the tactics used in such supply chain attacks.

SLSA: "Supply chain Levels for Software Artifacts". This is a framework designed for creating repeatable builds with provenance of their components.

OpenChain: an ISO standard for open source license compliance, developed and hosted by the Linux Foundation. It provides a set of requirements to create effective open source management systems, helping companies to minimize legal risks related to open source software use and improve efficiency and trust in the software supply chain.

Renovate Bot: Renovate Bot is an open-source tool that helps to automate the process of updating dependencies in software projects. It scans your project for dependencies, automatically opens pull requests to update outdated ones, and provides change logs and compatibility information to assist in validation and troubleshooting.

Secure Supply Chain Consumption Framework (S23C2F): The S2C2F SIG is a group working within the OpenSSF's Supply Chain Integrity Working Group formed to further develop and continuously improve the S2C2F guide which outlines and defines how to securely consume Open Source Software (OSS) dependencies into the developer’s workflow.

Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC): a non-profit organization dedicated to reducing cyber-risk in the global financial system. It enables members to share threat and vulnerability information, collaborate on incident response and mitigation, conduct synchronized response, and provides tools for better protection against physical and cyber threats.

Legislation

US

Following SolarWinds the US government became concerned with the issue of software supply chain security. See the linked articles below for more information. However, a very brief summary is as follows:

- Removing barriers to sharing threat information between different government departments and the private sector.

- Adopting a zero-trust architecture, deployment of MFA, encryption etc.

- Accelerate movement to secure cloud services

- Enhance Software Supply Chain Security, adopting the standards and best practices, SBOMs etc.

- Establish a standard "Playbook" for responding to cyber incidentts.

- Improving detection of cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents e.g. by deploying EDR

See:

- Bob Calloway - "All Things Open Keynote, 2022 on Supply Chain Security.

- OpenSSF's Blog Article about this legislation.

- Executive Order (2021) on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity

- Securing Open Source Software Act (2022). This bill sets forth the duties of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) regarding open source software security.

- FACT SHEET: President Signs Executive Order Charting New Course to Improve the Nation’s Cybersecurity and Protect Federal Government Networks]

EU

- EU Cybersecurity Strategy (2020) aiming to bolster the digital supply chain's resilience and security.

- Digital Operational Resilience Act (2020) ensure that all financial entities can withstand potential ICT threats, thus addressing the risks that ICT (including supply chain vulnerabilities) can pose to financial stability.

- EU Cyber Resilience Act (2022) regulation on cybersecurity requirements for products with digital elements.

UK

Further Reading

State of the Software Supply Chain - SonaType's 2021 Report

Open Source Software Supply Chain Security Report from 2020 by the Linux Foundation.

Do your part to secure the open source supply chain article by GitHub ReadME.

Keynote - OSS Supply CHain Security talk by Google's Bob Calloway at All Things Open 2022.

Protect your open source project from supply chain attacks - 2021 blog article adapted from talk at All Things Open 2021, in the form of a Supply Chain Security quiz.

CVEs article from the BoK.

SBOMs primer.

OpenChain Security Assurance an ISO Standard from the Linux Foundation.